Often the question is raised on what are the most impotant inovation during the last years

Not very common eduational innivations are mentioned. Imagine if you were asked to name the most important innovation in transportation over the last 200 years, you might say the combustion engine, air travel, Henry Ford’s Model-T production line, or even the bicycle. The list goes on. Now answer this one: what’s been the single biggest innovation in education?

Not very common eduational innivations are mentioned. Imagine if you were asked to name the most important innovation in transportation over the last 200 years, you might say the combustion engine, air travel, Henry Ford’s Model-T production line, or even the bicycle. The list goes on. Now answer this one: what’s been the single biggest innovation in education?

Don’t worry if you come up blank. You’re supposed to. The question is a gambit used by Anant Agarwal, the computer scientist named this year to head edX, a $60 million MIT-Harvard effort to stream a college education over the Web, free, to anyone who wants one. His point: it’s rare to see major technological advances in how people learn.

Agarwal believes that education is about to change dramatically. The reason is the power of the Web and its associated data-crunching technologies. Thanks to these changes, it’s now possible to stream video classes with sophisticated interactive elements, and researchers can scoop up student data that could help them make teaching more effective. The technology is powerful, fairly cheap, and global in its reach. EdX has said it hopes to teach a billion students.

Online education isn’t new—in the United States more than 700,000 students now study in full-time "distance learning" programs. What’s different is the scale of technology being applied by leaders who mix high-minded goals with sharp-elbowed, low-priced Internet business models. In the stories that will follow in this month’s business report, MIT Technology Review will chart the impact of free online education, particularly the “massive open online courses,” or MOOCs, offered by new education ventures like edX, Coursera, and Udacity, to name the most prominent (see “The Crisis in Higher Education”).

These ideas affect markets so large that their value is difficult to quantify. Just consider that a quarter of the American population, 80 million people, is enrolled in K–12 education, college, or graduate school. Direct expenditures by government exceed $800 billion. Add to that figure private education and corporate training.

These ideas affect markets so large that their value is difficult to quantify. Just consider that a quarter of the American population, 80 million people, is enrolled in K–12 education, college, or graduate school. Direct expenditures by government exceed $800 billion. Add to that figure private education and corporate training.

Because education is economically important yet appears inefficient and static with respect to technology, it’s often cited (along with health care) as the next industry ripe for a major “disruption.” This belief has been promoted by Clayton Christensen, the influential Harvard Business School professor who coined the term “disruptive technology.” In two books on education, he laid a blueprint for online learning: it will continue to spread and get better, and eventually it will topple many ideas about how we teach—and possibly some institutions as well.

In Christensen’s view, disruptive technologies find success initially in markets “where the alternative is nothing.” This accounts for why online learning is already important in the adult education market (think low-end MBAs and nursing degrees). It also explains the sudden rise of organizations such as Khan Academy, the nonprofit whose free online math videos have won funding from Bill Gates and adoring attention from the media. Khan gained its first foothold among parents who couldn’t afford $125 an hour for a private math tutor. For them, Salman Khan, the charming narrator of the videos, was a plausible substitute.

Khan’s simple videos aren’t without their critics, who wonder whether his tutorials really teach math so well. “We agree 100 percent we aren’t going to solve education’s problems,” Khan responds. But he says the point to keep in mind is that technology-wise, “we’re in the top of the first inning.” He’ll be pouring about $10 million a year into making his videos better—already there are embedded exercises and analytics that let teachers track 50 or 100 students at once. Pretty soon, Khan told me, his free stuff “will be as good or better than anything anyone is charging money for.”

Digital instruction faces limits. Online, you will never smell a burning resistor or get your hands wet in a biology lab. Yet the economics of distributing instruction over the Web are so favorable that they seem to threaten anyone building a campus or hiring teachers. At edX, Agarwal says, the same three-person team of a professor plus assistants that used to teach analog circuit design to 400 students at MIT now handles 10,000 online and could take a hundred times more.

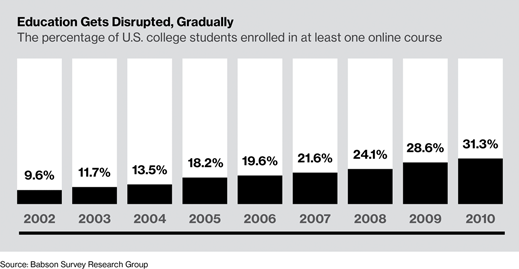

So where are we on the online education curve? According to a study from Babson College, the number of U.S. college students who took at least one online course increased from 1.6 million in 2002 to 6.1 million, or about a third of all college students, in 2010. The researchers, I. Elaine Allen and Jeff Seaman, found signs that the growth rate of online classes might be starting to slow. But their study didn’t anticipate the sudden entry of premier universities into online education this year. Coursera, an alliance between Stanford and two dozen other schools, claims that it had 1.5 million students sign up.

Even though only a small fraction of those will actually complete a class, the rise of the MOOCs means we can begin thinking about how free, top-quality education could change the world. Khan’s videos are popular in India, and the MOOC purveyors have found that 60 percent of their sign-ups are self-starters from knowledge-hungry nations like Brazil and China. Nobody knows what a liberal application of high-octane educational propellant might do. Will it supersize innovation globally by knocking away barriers to good instruction? Will frightened governments censor teachers as they have the Web?

Technology will define where online education goes next. All those millions of students clicking online can have their progress tracked, logged, studied, and probably influenced, too. Talk to Khan or anyone behind the MOOCs (which largely sprang from university departments interested in computer intelligence) and they’ll all say their eventual goal isn’t to stream videos but to perfect education through the scientific use of data. Just imagine, they say, software that maps an individual’s knowledge and offers a lesson plan unique to him or her.

Will they succeed and create something truly different? If they do, we’ll have the answer to our question: online learning will be the most important innovation in education in the last 200 years.

http://www.technologyreview.com/news/506351/the-most-important-education-technology-in-200-years/